Speaking with the Ancients

The conches sound and more than 1,700 faces turn seaward. It's an exceptionally

large turnout for this rural district on Hawaii's island of Oahu. They have gathered

here at Kahana Bay this February morning of 1997 to welcome the arrival of two

voyaging canoes: the Hokule'a and E'ala. The Hokule'a, built 22 years ago to

test the hypothesis that Hawaiians had sailed to these islands without navigational

instruments, proved the theory correct in 1976 when it sailed to Tahiti and back.

More than that, it inspired many Hawaiians to turn toward their cultural roots

and take pride in their past.

Now the Hokule'a is on the second leg of a statewide voyage to demonstrate

Hawaiian navigation and to serve as a focal point for community activism. Along

with their skilled crews, both canoes sail with community representatives and

local high school students aboard. And during the visit, the public is invited

to learn about voyaging education at the beach, take canoe tours, or stargaze

with the Polynesian Voyaging Society staff.

Students from area schools visit the canoes to learn about sailing and navigation,

and about the ancient values that anteceded those skills—values like 'ohana

(extended family), malama (caring) lokahi (harmony, unity), and

laulima (many hands working together to accomplish a common goal).

For several months preceding the visit, the community of Ko'olau Loa on Oahu's

north shore, which helped sponsor the event, worked together in a massive effort

to make the celebration a success. Up and down the coast, hundreds of volunteers

prepared the welcome of the Hokule'a with traditional Hawaiian protocol that

included chanters, dancers, musicians, and a luau for 1,700 people.

All this spirited activity came from a community that only a year before had

questioned their ability to cooperate, to inspire any real cohesion. What changed

during that year can be found in the story of a people who reached into the past

to rebuild their future. The celebration for the canoes is only one expression

of a wider effort to restore community values in Ko'olau Loa, an effort that

grew out of a future search conference held in February 1996.

An endangered species

An understanding of why renewal of ancient values is so crucial to building

a healthy community in Ko'olau Loa— and what it has to do with modern healthcare

requires a brief look at Hawaiian history. For centuries, the Hawaiian Islands,

relatively isolated from the rest of the world, maintained their traditional

way of life. But during the 19th century, life for the islanders changed drastically.

Early in the century, missionaries and traders brought foreign diseases to

which the islanders had no immunity. Hawaiians died in staggering numbers. By

mid-century the native population had fallen 90 percent, from an estimated 500,000

to about 50,000.

To save her people from extinction, Queen Emma, along with her husband King

Kamehameha IV, started The Queen s Medical Center, now Hawaii's largest health

facility. When Queen Emma died in 1885, she left vast land holdings to support

healthcare of Hawaii's people.

Exotic diseases were not all the missionaries and other outsiders brought.

The Hawaiian way of life altered dramatically with the influx of new religious,

social, and business practices. Western values of competition, individualism,

and power clashed with Hawaiian values of harmony and mutual support.

Soon outside markets, not local need, drove the Hawaiian economy. Much of Oahu

was redistricted into sugar and pineapple plantations. As society stratified

along economic lines, native Hawaiians became an economic underclass, with attendant

physical and social calamities.

Now, more than a century later, the legacy of Westernization is evident in

continuing social and medical problems. According to October 1995 statistics

from The Queen Emma Foundation, ethnic Hawaiians, 12.5 percent of the state's

population, account for 50 percent of teen pregnancies and 44 percent of asthmatics

under age 18. They have the highest diabetes rate for those 35 years and older

(44 percent); 42 percent are overweight; and 40 percent are acute or chronic

drinkers.

Their young people have a juvenile arrest rate 33 percent higher than other

citizens.

What the community wants

A heavy concentration of ethnic Hawaiians— 24 percent of 20,000 residents—live

in Ko'olau Loa on Oahu's north shore, along with people of Caucasian, Chinese,

Filipino, Japanese, Samoan, and other descents.

Ko'olau Loa's seven coastal villages retain separate identities, but all were

shaped by ancient values. Centuries ago, the land was divided into sections called

ahupua'a, which extended from the top of the mountain to the sea. Each

ahupua'a supported all life-sustaining activities—hunting, fanning, and

fishing—so that families living there had access to resources that enabled them

to be self-sufficient.

In 1994 the Queen Lili'uokalani Trust invited The Queen Emma Foundation to

build a medical clinic at its children's center in Ko'olau Loa. The Foundation

staff held town meetings in each village and asked what the community wanted

and whether they wanted the Foundation in their area. The staff were surprised

to learn that residents wanted more than medical care: They spoke about education,

jobs, family, recreation, safety, community values, and quality of life.

The villages, the Foundation learned, shared an ancient culture based on family;

community well-being; commitment to a place of refuge (pu'uhonua); oneness

with the earth; and unity of body, mind, and spirit. This was demonstrated in

the Hawaiians' rich, value-laden vocabulary. The word laulima, for example,

means many hands working together to accomplish a common goal. Ho'opono

means to make things right. Lokahi means harmony, unity—of spirit, mind,

and body.

They also shared a legacy of mutual suspicion and distrust of "outsiders"—even

citizc-ns of other district villages.

Despite its rural character, Ko'olau Loa also is home to two major Mormon institutions,

Brigham Young University's Hawaii campus and the Polynesian Cultural Center,

which attracts more than a million visitors a year. A coalition of environmental

groups had recently sued the church's land management company to prevent the

expansion of a sewage treatment plant adjacent to an ancient heiau, a

religious site. Many Hawaiians are also Mormons. The issue had become a divisive

one in Ko'olau Loa.

A radical integration

The Foundation proposed an ambitious healthy communities plan for Ko'olau Loa,

based on a conceptual model that renewed ancient values in a modern context.

In the traditional culture, families and communities supported each other and

turned to institutions only when the other options had been exhausted. In the

modern culture, institutions, government, and professionals had taken over and

depersonalized human services.

The Foundation suggested that the community explore ways to actualize the older

model in the context of modern services in order to create a radical integration

of services. In the proposed model, people would find support at every level.

When a family (hale) and extended family ('ohana) were unable to

cope, there would be a pu'uhonua to go to for care - short-term care,

daycare, outpatient services, counseling, respite, or some combination thereof.

This modern place of refuge would look more like a community center than a government

agency or medical facility.

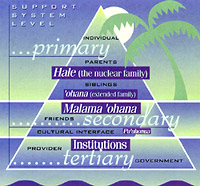

The

figure shows a cultural support chain based on levels of access. All these levels

were conceived as bound together in an interdependent union (lokahi)

of body, mind and spirit. The Foundation imagined it would take at least two

years to develop a networking plan and to find concrete projects that people

could do together. But where and how to begin?

The

figure shows a cultural support chain based on levels of access. All these levels

were conceived as bound together in an interdependent union (lokahi)

of body, mind and spirit. The Foundation imagined it would take at least two

years to develop a networking plan and to find concrete projects that people

could do together. But where and how to begin?

"The communities wanted more than a medical facility," explained Hideo

Murakami, senior vice president of the Foundation. "They wanted an infrastructure

that made for a better quality of life. We knew how to put up a clinic. But empowerment?

Values? We had great difficulty translating these abstractions into concrete

projects."

Having revived the concept of lokahi, or unity, in its proposed model,

the Foundation decided to make a radical shift in its approach to the community.

To help Ko'olau Loa devise forms of cooperation and substantive projects true

to its ancient traditions, they decided to explore the possibility of a future

search conference. This involves four basic principles:

- Get the "whole system" in the room.

- Put local issues in a global context.

- Make future action the goal, treating problems and conflicts as information

rather than action items.

- Self-manage and organize to do whatever participants cleciclc.

The future search agenda includes: a joint exploration of the past, present,

and future; an acknowledgment of common ground and differences; action planning.

No training. conceptual models, or expert inputs are required. People meet on

a level playing field where everybody's views, languages, experience, and values

count. (For a more detailed description of this approach, see "Future Search:

A Power Tool for Building Healthy Communities," in the May/June 1995 issue of

this journal.)

Several months before the conference was scheduled, one of us met with a steering

group of ten residents and other stakeholders, many from families who went back

generations. They talked about the struggles facing Ko'olau Loa: The seven villages

were scattered along a 24-mile road. For many people, schools, clinics, daycare,

and shopping were long distances away. The local hospital's obstetrics department

and a preschool program had closed for lack of funding. The sewage treatment

plant conflict upset many people. While they shared concerns for the future,

wary residents displayed little communal spirit. They were skeptical of their

own capacity for cooperative action.

Nonetheless, the planners identified future search as an appropriate way of

framing ancient practices—sharing food and rituals, storytelling, honoring the

whole person, involving everyone in making things right, and building a safe

world for the children.

Early on, the planning committee made two critical decisions: (1) to bring

together people on opposing sides of the most divisive issues (land developers

and community activists, for example), and (2) to ensure that the event would

embody traditional Hawaiian culture and heritage.

A wise elder, Auntie (a title of respect) Malia Craver, was named conference

kupuna to share her wisdom and spirit when needed. Throughout the planning,

she was the calm at the storm center of questions, excitement, and skepticism

about this "method from the mainland.''

Ho'opono Ko'olau Loa

The future search took place in February 1996. It was called 'Ho'opono Ko'olau

Loa: A Community Effort to Restore Community Values." The Queen Emma Foundation

and Queen Lili'uokalani Trust provided the resources. Participants included high

school students, teachers, native Hawaiian healers, providers from local hospitals,

clergy, community associations, social and cultural agencies, business people,

activists, and residents of all ethnicities. Every participant received a lei

made by local residents. Auntie Malia opened and closed each session with a Hawaiian

prayer.

During two-and-a-half intense days, 73 people reviewed their personal histories,

and that of the society and the community going hack many decades. They explored

shared concerns about education, drugs, the decline of family, the clash of traditional

and Western values, collaboration and partnerships, land ownership and development,

the disenfranchisement of youth, and unemployment. People talked about what they

already were doing about their concerns, and what they wanted to do in the future.

Then, they "dramatized" the community they all wanted to live in, acting out

scenarios of local life in the year 2020. By the third day, participants were

astonished at the degree of unanimity: They agreed they would seek to maintain

the rural nature of the community, integrate traditional and Western medicine,

start a community-controlled wellness center, develop schools as lifelong learning

centers, set up a pu'uhonua (place of refuge) and a cultural center in

each town, and initiate community-based development projects.

In traditional planning meetings, people often narrow down to a few priorities

In future search, with all aspirations and potential projects on large chart

pads, we ask, "Who wants to do what?" Then people vote with their feet.

When the question was asked in Ko'olau Loa, a critical dialogue on the Foundation's

role followed. Would the Foundation continue to lead? Would they fund whatever

was needed?

At last, a respected resident said, "Let's see what we can do for ourselves,

and then we can see what help we need. We cannot keep on relying on everything

from outside the community." Many heads nodded and several spoke up, acknowledging

the need to reshape their relationship with outside organizations. The Foundation

agreed to help with the transition if citizens would take the initiative.

Volunteers formed six task forces. One would link existing community associations;

another would initiate a health and wellness program integrating traditional

and western medicine. Still others signed up to create a master plan to address

social, economic, and environmental issues for the district; initiate community-based

education; involve youth in civic affairs; and build a pu'uhonua in each

town.

With the Foundation's help, they started a newsletter for all residents, and

the original planning group expects to expand and apply for nonprofit status

so that they can raise their own funds.

Eight months after the conference, we called several residents to find out

hc \\ thuy ~;crc doing. The cooperative spirit released by the future search

continues to ripple through Ko'olau Loa. The implications for community health

are far-reaching.

Modern medicine welcomes native healers

The Health Committee in Ko'olau Loa is seeking to integrate Hawaiian values

and practices into the dominant Western medical model. For centuries, Hawaiian

leaders used prayer, massage, and herbs to restore balance among mind, body,

and spirit. Then, 80 years ago, it became illegal to practice native medicine.

Hawaiian healers went underground. And there they remained until 1993, when President

Clinton signed a bill that legalized native cultural practices.

Today, all traditions are valued by Ko'olau Loa's Health Committee. For the

first time, a broad spectrum of providers is involved together in rethinking

how they deliver services. "We had been walking on separate traits," said one

resident. "Now a great many of us have found a common path."

"There have been specific community efforts all along. Like prenatal care and

drug abuse prevention," says Laura Armstrong, a member of the Health Committee,

who is chief of the Community Health Nursing Division in the state department

of health. "But many people, even those with difficult problems, often don't

show up at the clinic. We have to stop looking at them as noncompliant and start

looking at the barriers that the system has created."

Some Western doctors, she pointed out, don't want to know what traditional

practices people follow. Many patients don't tell medical doctors about the other

healers they visit. "The health committee sees its work as creating an umbrella

so that the values talked about at the conference come first," Armstrong adds.

"The program I run incorporates culture into native care. We have Japanese,

Hawaiian, and other healers developing protocols with us for public health nursing.

No longer can we say that we nurses are the bosses and we know what is best.

We are changing our nursing curriculum to emphasize patients and families as

partners. The Ko'olau Loa experience was the turning point. It's a whole new

mindset."

In addition the community is identifying traditional healers, most of them

elders who until recently were not free to pass on their practice. Creating a

directory of native healers is not as simple as it seems. "You can't just list

them in a yellow pages book," says Herb Wilson, a committee member and a teacher

at Kamehameha School. "That would contradict how they work. How can you identify

them but not violate their values?"

In parallel, young native practitioner Bulla Logan and his teacher, elder Norman

Kaluhiokalani, are producing a videotape to educate the HMO system about traditional

medicine. They also are working with the Board of Health on compliance standards,

following precedents set by the Canadian system, which recognizes Indian medicine.

Another aspect of this effort is creating awareness that healers exist in every

family. "That doesn't mean just one person," says Armstrong. "Every one takes

his and her turn. For example, a child who learns that smoking is bad for you

and tells the family becomes the healer." Cultural healers, she says, are an

essential part of every community and of every home. Many families have passed

this notion down through generations. Many others have no awareness.

"We also want to come up with what people in the community define as healing

families," says Armstrong. "We want to come together with our education group

and our pu'uhonua group," she adds. "The Master Plan committee is meeting

with us, too, and we will make sure they don't forget about health."

Healing connections

What happens when people coordinate their own projects is vividly illustrated

by the ways in which the many activities intersect. In a joint meeting, for example,

the Pu'uhonua Committee and the Health Committee concluded that traditional heaters

should offer services in each new pu'uhonua.

Meanwhile, Gwen Kim, a planning group member, set up a healthy lifestyle project

for community residents at the Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center. Entire

families are invited to a 21-clay series where they learn how to prepare a healthy

Hawaiian diet, including such traditional foods as taro. Now residents are identifying

the Children's Center as a place to go for help, the first new pu'uhonua.

Kahuku Hospital, Ko'olau Loa's main medical center, also has started a community-wide

effort to focus on prevention and good health practice. Every second and fourth

Saturday of the month they hold a Health Fair/Farmer's Market in the district.

They are screening for diabetes, high blood pressure, and other diseases while

providing a place for farmers to sell their produce.

"Hawaiians have a very poor health record," says Auntie Gladys Pu'aloa-Ahuna,

a member of the planning group. "We are among the highest of all ethnic groups

in cancer, AIDS, high blood pressure, diabetes - all the diseases that kill.

It's very grim. But things are moving in a positive direction. The network is

spreading. We are experiencing more concentration on health and a greater willingness

to get involved. "

"What's going to happen to our children?"

Maxine Kahaulelio, a local mother and cook at Hau'ula Elementary School, had

fought for six months to keep the Kamehameha Preschool Program alive after it

lost its funding. "I just couldn't accept that these little children and their

mothers - a lot of them young themselves - would not have this kind of opportunity

anymore," she said. "What's going to happen to our children?"

She found allies in child psychologist Marsha Deforest, retiree John Kaina,

public health nurse Lynn Chang, and housewife Keoana Hanchett. By the time of

the future search, the five had a dream and no resources. Then life-long learning

emerged as a shared value. "It hit me during the conference," said Kaina. "I

became convinced that people can work together."

Kaina counts himself an unlikely advocate for childhood education. "I worked

for Hawaiian Electric for 42 years, starting right after high school. I worked

poles, towers, flying in helicopters stringing wires over mountains. Early education

is a whole new ballgame for me. At the future search conference, I was nervous.

I thought, 'What am I doing here?'

"Then I stood up and told what my table had come up with. When I got through

it, I felt much better. By the end, we had a plan."

Applying what they had learned about citizen involvement at the future search,

the five called a parents' meeting. It was standing room only. Their steering

committee quickly expanded to 25 and now includes parents, educators, health

professionals, and funders. They soon got a $40,000 grant from the John A. Burns

Foundation, and space, materials, and technical support from the Queen Lili'uokalani

Children's Center. They named themselves the Ko'olau Loa Early Education Program

(KEEP). Auntie Malia Craver suggested adding to the name na kamalei, meaning

the precious children." In September, Na Kamalei KEEP opened with 31 preschoolers,

a full-time teacher, and two aides. "We started with nothing, and now we have

school going," says Kaina.

Na Kamalei provides play activities, excursions, use of English and Hawaiian,

music, storytelling, creative arts, and parenting skills education. To breathe

life into the concept of malama 'ohana - a cultural care network - Na

Kamalei has joined three other child development programs: Malama Na Wahine Hapai

provides prenatal care; Healthy Start visits mothers of infants and toddlers

at home; and Healthy and Ready To Learn works with families to teach good health

practices.

"We want our children to be picked up at the beginning, to be educated, and

to grow in a healthy way," says Kahaulelio. "Our whole community is joining hands.

We don't want the kids to slip through our fingers again."

A reason to stay

Another citizen who came away from the future search determined to plan with

"the whole system in thc room "

was Kahuku High School principal Lea Albert. The school's 2,045 students make

up 10 percent of Ko'olau Loa's population. Concerned that so many young people

abandon the community when they graduate, Albert called a three-day school planning

summit. There, 140 parents, teachers, students, business people, and staff considered

the implications for public education of the common ground identified in the

earlier conference.

As a result, Kahuku High is adding many community-based themes to its curriculum.

Topics include healthcare as a future industry for the area, integrating Western

and traditional medicine, protection of the environment, agriculture, eco-tourism,

water and waste management, and housing. "We want our students to live here after

graduation, buy homes here, and make career choices that relate to the economic

future of the region," says Albert. "This is one of the most beautiful places

on earth and our youngsters can help in managing the resources that keep it that

way."

In addition, young people from the Ho'opono Ko'olau Loa future search have

organized their own initiative. Spearheaded by Christian Palmer, a recent Kahuku

High graduate now at BYU-Hawaii, their goal is to have more input on community

decisions. The group includes at least one student from each grade level and

one from every town. They attend neighborhood association meetings and convene

monthly.

"We want to offer a youth point of view," says Palmer. The group is planning

a "community convention" of students from all the towns to begin breaking down

barriers. "The Ho'opono Ko'olau Loa conference was an eye opener," says Palmer.

"My friends and I realized our community's future is determined by the people

who are active and interested."

A warmer, wiser community

Clearly the citizens of Ko'olau Lau have made a dramatic shift in their capability

for improving community health by reconnecting with traditional Hawaiian values.

Moreover, they have engaged hundreds of residents from diverse cultural backgrounds

in a wave of cooperation including healthcare organizations, schools, churches,

youth groups, businesses, foundations, and government agencies. The projects

they have undertaken represent a new spirit of cooperation, initiative, responsibility,

and optimism that crosses the boundaries of geography, ethnicity, economic status,

occupation, and age.

Not all of Ko'olau Loa's dilemmas, of course have been solved. What has happened

so far is based on what people are ready, willing, and able to do now that they

have found each other and reconfirmed their values. Many intractable issues remain.

Not the last of these- is the matter of the sewage treatment plant. Environmentalists,

even those at the conference, remain adamantly opposed. What's new is that the

parties are talking with each other.

Conference participant Eric Shumway, president of BYU-Hawaii, put it this way.

"There's an old Hawaiian saying that 'you don't grow taro in six weeks.' But

the seeds that were planted at the conference are sprouting in unexpected areas.

We are no longer strangers to each other. We are a much warmer community, and

that is critical."

The way the community worked together for the celebration of the canoes is

one expression of that warmth. Gladys Pu'aloa-Ahuna, an elder from the area,

called the event "a binding—tying us to each other and tying us to our past,

to our kupuna - our ancestors."

|

SANDRA JANOFF, PhD and MARVIN R. WEISBORD are coauthors of Future

Search: An Action Guide to Finding Common Ground in Organizations and Communities

(Berrett-Koehler, 1995). They are co directors of Search Net, a nonprofit network

that provides affordable services to nonprofit community organizations to help

them envision and implement attractive futures. They can be reached at (215)

842-2842. |

The

figure shows a cultural support chain based on levels of access. All these levels

were conceived as bound together in an interdependent union (lokahi)

of body, mind and spirit. The Foundation imagined it would take at least two

years to develop a networking plan and to find concrete projects that people

could do together. But where and how to begin?

The

figure shows a cultural support chain based on levels of access. All these levels

were conceived as bound together in an interdependent union (lokahi)

of body, mind and spirit. The Foundation imagined it would take at least two

years to develop a networking plan and to find concrete projects that people

could do together. But where and how to begin?